Does Sweden Have Rule Of Law?

The stars have aligned in a strange way over Sweden and something quite out of the ordinary has happened: a former director of a government authority has started to talk openly about the de facto legislative process that goes on within the executive branch of the government. She seems to be arguing, in court, that her decision to suspend certain laws should have been respected by the judicial system, that it was an everyday occurrence, and that her employment at the highest levels of the executive branch should not have been terminated as a consequence of her actions.

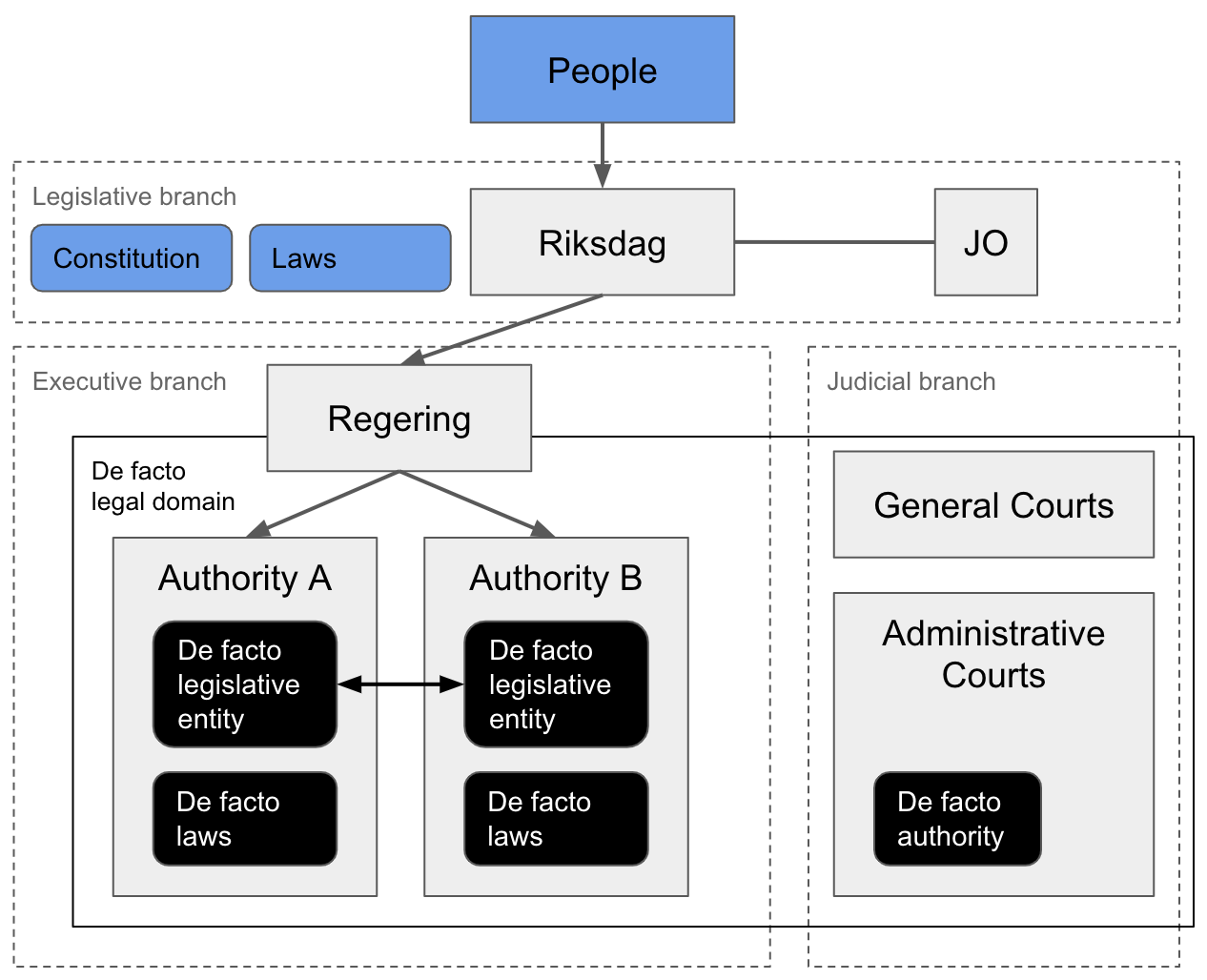

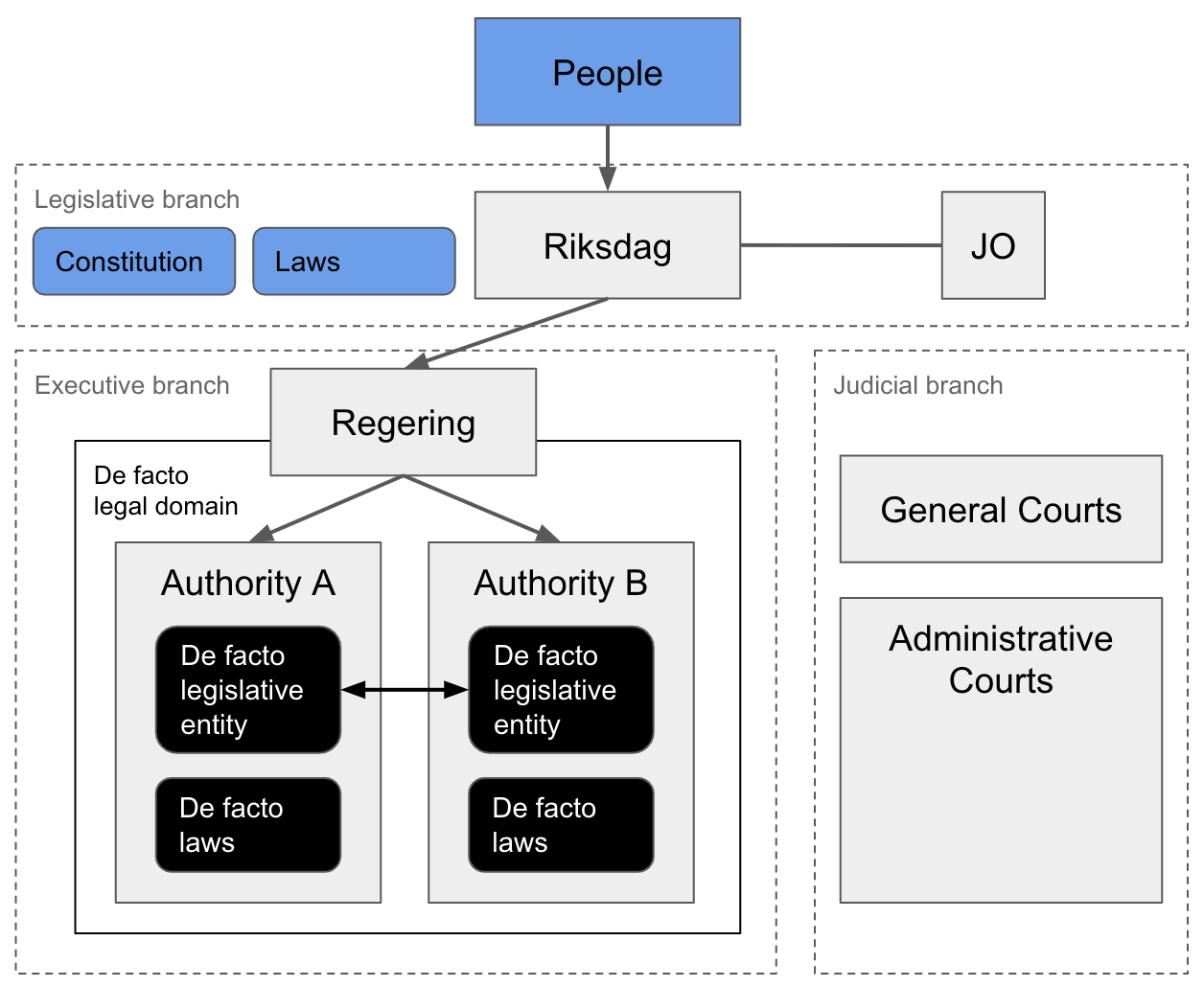

With this information we can infer a number of models of the Swedish government that could describe how the state actually functions. The most extreme model inferred in this post is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The most extreme model of the Swedish de facto system of government inferred in this post. Blue parts are fully public. Grey parts are the relevant de jure government bodies. Black parts are inferred de facto bodies of government. The Regering, or it's employees, seem to be somewhat in control of the de facto legislative entities. This makes it possible for the executive branch to suspend rule of law when it is deemed necessary. This is not ordinary corruption, but rather an organized state within the state. It's seemingly used to ensure that the state operates efficiently, and is more effective than would be possible de jure. In this extreme model the de facto laws passed within the authorities sometimes (de facto) decide the outcome of court cases. In an attempt to prevent this the administrative courts sometimes do the work that should de jure be performed by the authorities. This work is performed within the de facto authorities inside the administrative courts, in compliance with the public laws.

If this model, or a similar one, is an accurate description of the Swedish de facto system of government, then some questions arise: Is this system really reconcilable with the classic definition of rule of law? If not, does Sweden deserve its reputation for strong rule of law? Could it be that this organized suspension of the rule of law has strong benefits that can partly explain the effectiveness of the Swedish government? If so, is Sweden preaching one thing to the world, and practicing another? Many more questions arise of course.

If a model similar to those proposed here is an accurate description of the Swedish de facto system of government, then my personal experiences interacting with this system become much easier to explain. This of course is a mixed blessing in this context: when a model explains your personal experiences it is easy to place too high a posterior probability on the uncertain proposition that the model is correct in an objective sense. Is this really science? At the same time, experiments are in a philosophical sense personal experiences. It’s not entirely clear to me where the line should be drawn between the subjective and the objective.

This post is labeled within two categories: probability theory and social science. The methodology here comes largly from subjective probability theory and is inspired by Jaynes (2003). If this post results in any novel contributions then they would probably fall within fields like political science, jurisprudence, economics and perhaps even sociology. There could also be a contribution to the study of methodology within social science as a whole. If so, then it can perhaps be described as an application of a hypothetico-deductive method to the social sciences. I should be clear that nothing in this post proves to me that any of the models presented here are correct. To me they are only plausible, given the data I have today and the interpretations of that data I can currently see. I could change my mind tomorrow.

Figure 2. The methodology behind this post is inspired by Jaynes (2003), his treatment of plausible reasoning and the concept of the Robot introduced in the book. Note that Jaynes thought that it would be reasonable for the Robot to reason about the proposition that Beethoven and Berlioz never met. As I see it that requires a model of social reality, similar to the models I try to reason about here. Note also that Jaynes thought that the Robot concept should not be used to reason about the plausibility of a proposition decribing the relative qualities of different musical works. I will do my best to avoid that here. I therefore do not go very deep into the question of whether or not this is a good way to run a country. I feel a different methodology is probably required in order to answer such questions.

I try to outline here how a rational agent like the Robot could in principle reason about social reality and infer models of it. There could possibily be a contribution to the field of artificial intelligence here, but I don’t know to what extent my thinking aligns with current research in this field. If you’d care to enlighten me, please contact me on Twitter. I guess cognitive science and psychology deal with similar questions. I’d love to hear some views from those angles too.

Historic Background

I start with a historic background, so that you can get a feel for the prior probabilities that I place on different possible models of the Swedish system of government. If you feel this is an incorrect, biased or irrelevant summary of historical developments, then you should question the probabilistic reasoning further below. In that case you place entirely different prior probabilities over the possible models and are unlikely to interpret data in the same way as I do. This doesn’t mean either of us is wrong. We just see the world differently. I’d love to hear your thoughts on Twitter.

Sweden is still formally a monarchy, and democracy developed here in a different way than in may other countries. If you go back to medieval times the king’s power was largely unconstrained by the laws. The first meeting said to bear any resemblance to today’s parliament, the Riksdag, was held in 1435. I think most historians would agree that the Riksdag’s power from then on slowly grew, at the expense of the king’s. In 1809 the first constitutional law that clearly separated power between the Riksdag and the king (“regeringsformen”) was passed. As part of that reform the courts and the government authorities were granted some independance from the king, and an ombudsman called Justitieombudsmannen was instated. People who felt wronged by the king, the authorities or the courts could turn to this ombudsman with their complaints. The inspiration for this system of government is said to have been the thinking of the french political philosopher Montesquieu and his thoughts on the separation of powers.

However, to the best of my knowledge there was really never any strong popular uprising against the king’s authority, similar to those in England, France or the United States. The king’s power was seemingly questioned by the elites, and slowly transferred to the Riksdag in law, but it seems to me a reasonable assumption that the average citizen held the king in quite high regard and felt no urgent need for this process to take place. It seems plausible to me that informal power thus remained with the king to a rather high degree, and that this informal power was then transferred to the central executive branch of the government, the Regering, in another slow process. The concept of rule of law thus never gained widespread popular support.

This second process was finalized in 1974 when the most central of our constitutional laws (“regeringsformen”) was changed so that the king could no longer “Rule the Kingdom alone”. The new wording states that all public power in Sweden derives from the people. This statement seems to be very important to many Swedes.

The same paragraph also states that all public power in Sweden is excercised under the laws. This is as I see it the clearest single statement in Swedish constitutional law mandating that the executive branch respect the Riksdag’s role as the national legislature and the supreme decision-making body of Sweden. To me this is also the clearest single statement mandating that the executive branch respect the rule of law (“rättsstaten”). However, I’m a 40-year-old Swede, and I can’t remember being thought this in school, or hearing any public discussion on the importance of this statement. This of course makes me somewhat unsure about the interpretation. I haven’t put any massive amount of time into researching the legislator’s intention. But it also makes me think that not many Swedes see the rule of law as very important.

The above makes me think that a relatively high prior probability should be placed on models in which the executive branch of the government is less constrained by law than it perhaps should be de jure.

The Standard Model of Government in Sweden

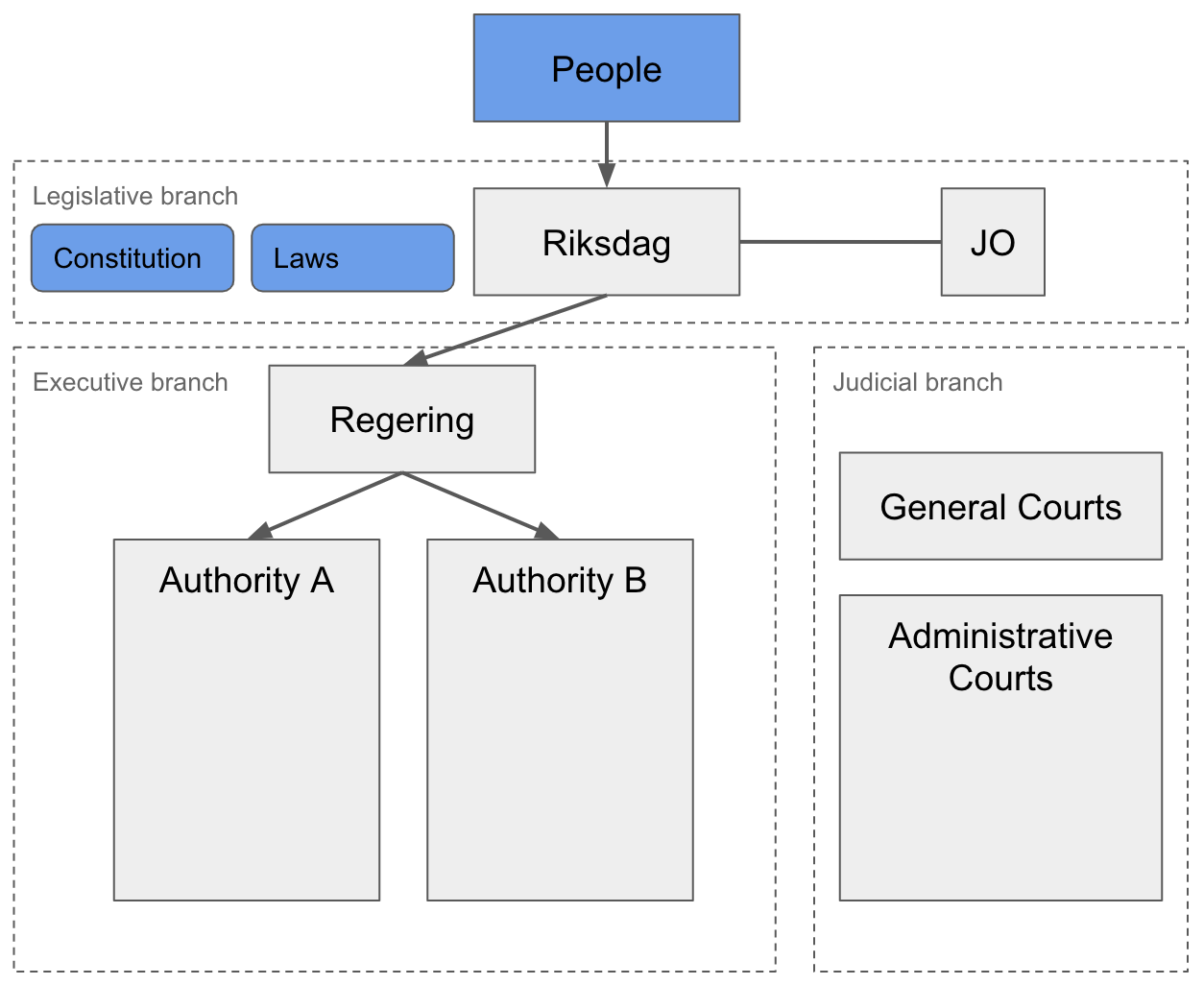

From the written laws we can derive a standard model of government in Sweden (see Figure 3). This is fully reconcilable with e.g. official information material on the Swedish system of government.

Figure 3. A de jure model of the Swedish system of government. The people elects the Riksdag. The Riksdag makes law, constitutional as well as ordinary. The laws are written and public. The Riksdag tolerates the Regering. The Regering appoints the director of the authorities under the Regering, like Authority A and Authority B. Authorities are ensured some independence under constitutional law, but are to a large degree controlled by the Regering. Authorities like A and B must comply with the laws. There are two types of courts, the general and the administrative, and these operate relatively independently of the executive branch. The Justitieombudsmannen (JO) receives complaints from the people, and performs investigations to ensure that the courts and the authorities follow the law.

New Data That Is Hard To Explain

The events surrounding the former director of the Swedish Transport Authority, Maria Ågren, are very hard to explain under the standard model of the Swedish system of government. The information below comes from a media report on statements Ågren has made in a court hearing. She seems to have been herd under a relatively mild oath (“sanningsförsäkran”).

In late 2015, when it was becoming apparent that an IT project within the transport authority would be delayed unless Ågren ordered that a so-called “deviation” (“avsteg”) from the law should be made, Ågren issued four formal orders. These seem to have contained instructions on which laws should temporarily be suspended within the authority.

Ågren has previously acted as director of two other government authorities. She claims that “deviations” such as the ones she seems to have issued within the transport authority where common there, even in cases concerning e.g. lawfull posession of firearms. When asked why she did not inform the Regering about these “deviations” she answered that this is not common practice, that the information was “sensitive” and that the Regering would be flooded with such information if all “deviations” were reported.

In this specific case the “deviations” had national security consequences, and the Swedish Security Service therefore took an interest in them. Ågren was informed of this, but at that stage the project was just days from completion, and she seemingly felt that this “deviation” was justified. It seems clear that she did not stop the project or recind any of her four orders. When she was contacted by the security services again in Febrary 2017, this time to notify her that she was formally suspected of a crime, she was “very chocked” (“väldigt chockad”).

Her union is apparently arguing that this culture of rampant “deviations” (“utpräglad avstegskultur”) is a normal part of the Swedish model of government.

It should of course be considered here that Ågren and her union have an economic incentive to exagerate the extent of this culture of rampant “deviations”: they are pursuing a claim against the state for wrongful termination.

Models Under Which The Data Is More Likely

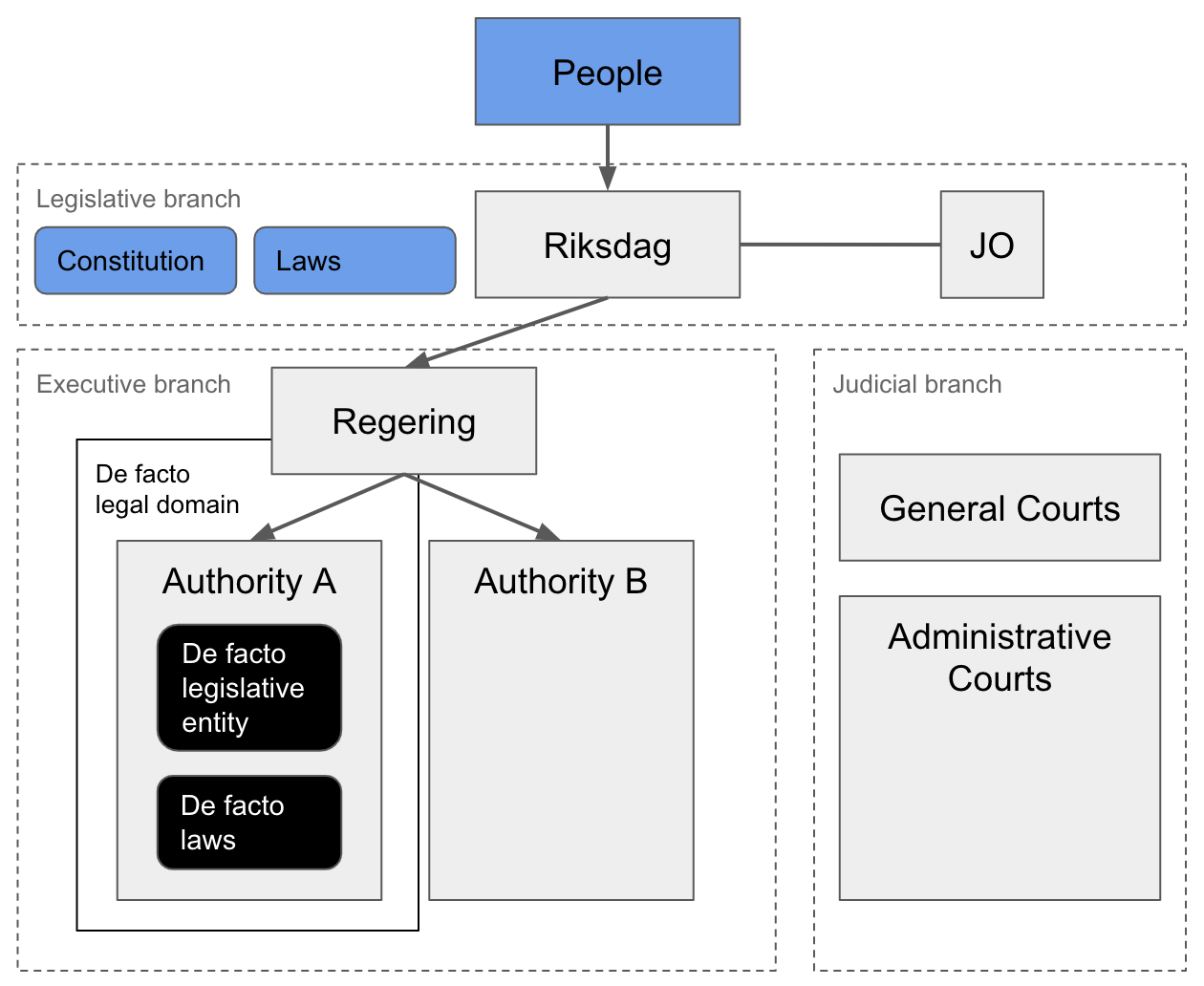

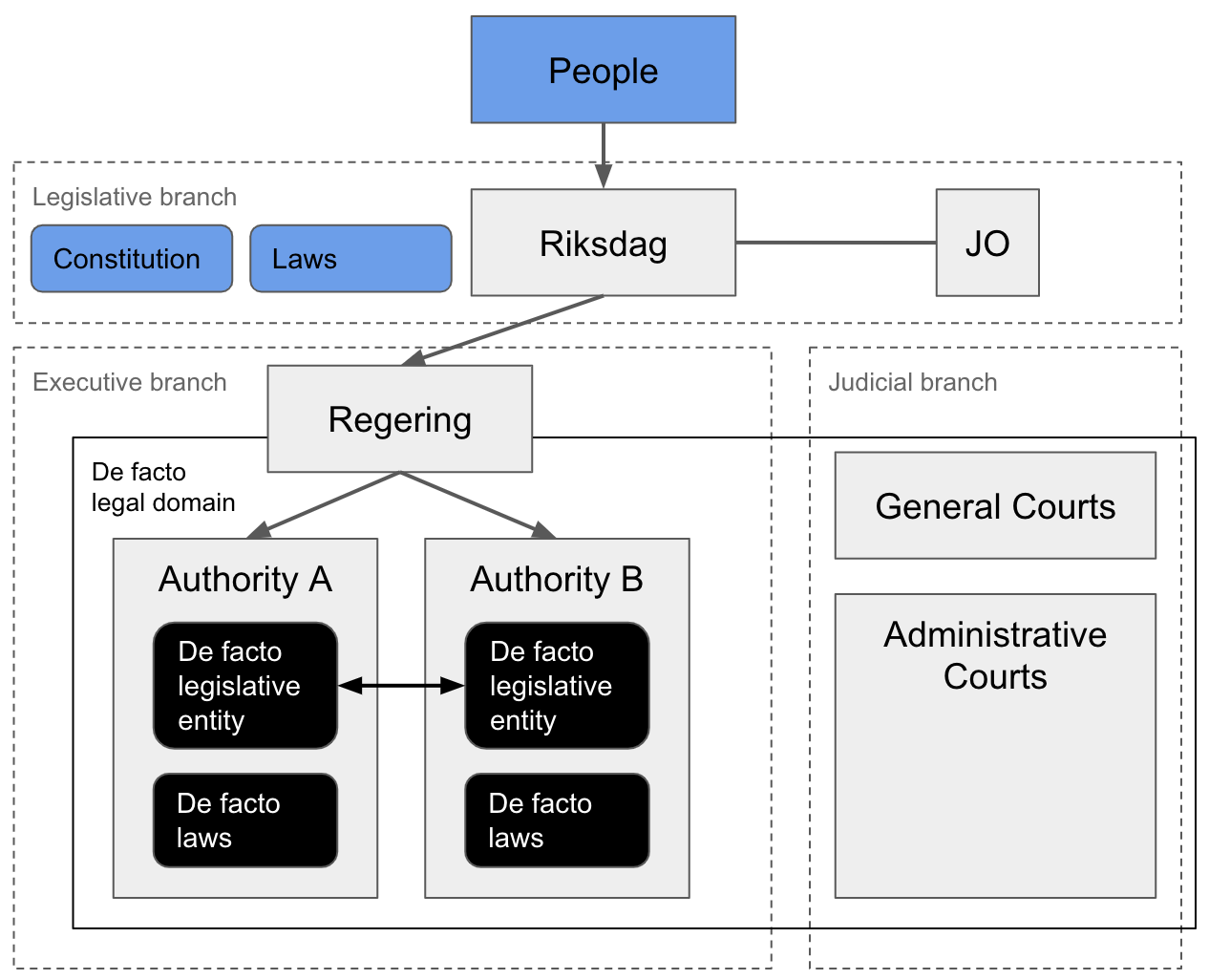

It’s quite clear that the statements above, if truthful, are very hard to explain under the standard model of the Swedish system of government. Arguing along the lines of the Robot in Jaynes (2003) we should therefore consider other models, under which the data is more likely. Such a model is presented in Figure 4. This can be seen as a form of bayesian inference. The model in Figure 4 was of course always a possible model of political life in Sweden. The only thing that has happened is that we now place a higher posterior probability on that model.

Figure 4. A first model of the Swedish de facto system of government. The difference compared to the de jure model is that we have inserted a de facto legislative entity and de facto laws into Authority A. The director of Authority A is seemingly somewhat in control of the legislative entity within the authority. The de facto laws apply within the de facto legal domain. In this model that domain is restricted to the authority itself and its interactions with the people.

It’s somewhat uncertain how de facto laws are stored within authorities. According to media reports of claims made by Ågren’s union the transport authority had a well established culture for temporary legislation of this kind, and even formal document templates for the de facto laws.

It is also somewhat unclear who is normally part of the de facto legislative entitiy. In this case at least one of the de facto laws seems to have been proposed by the head of security (“säkerhetsskyddschefen”), and passed by Ågren.

But it’s still, under this model, hard to explain why Ågren was so surprised when she heard that she was suspected of a crime. She seemingly knew that the security services had their eyes on the situation. She seemingly knew that the authority’s de facto legislative entity had temporarily suspended some public laws. Assuming she was reasonably rational in Jaynes’ sense of the word, it seems her model of the Swedish de facto system of government must have been different. One possible model that could explain her surprise is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. A second model of the Swedish de facto system of government. The difference compared to the first model is that we have inserted a de facto legislative entity and de facto laws into Authority B as well, and also connected the two de facto legislative entities to indicate that there could be communication between them, either directly or through the Regering. The de facto legal domain is now extended to include both Authority A and Authority B. The two authorities form one legal domain within which the de facto laws of both authorities are respected.

This second model could explain Ågren’s surprise: When she was informed that the security services (Authority B) were concerned about the de facto laws within her authority (Authority A) she seems to have taken the step to keep one of the Regering’s employees, Erik Bromander, informed of the situation. Perhaps she assumed that he would relay this information to the security services and that the link between the two authorities’ de facto legislative entities was now established. Perhaps she assumed that the two authorities were now operating within one de facto legal domain, and that the de facto laws she had passed would be respected by the security services. When the security services notified her that she was formally suspected of a crime she was surprised, because that meant that this model of reality was not correct in this specific case. This seems like a somewhat plausible explanation to me.

If that is the explanation we can infer some other things about this model of the Swedish de facto system of government: not all authorities have the same culture around de facto laws. The security services do not seem to always respect those of other authorities, at least not when they put national security at risk to save a few bucks. Also, for this to have happened it seems to me that either the information about the transport authority’s de facto laws was not relayed to the security services, or the message that the de facto laws would not be respected was not relayed back. Otherwise Ågren would probably have recinded her orders and stopped the IT project. She claims she was never informed that there could be criminal liability (other than through the public written laws of course). Could it be that the security services believe in the rule of law?

Finally there is one more data point here that is hard to expain even under the model in Figure 5: Ågren and her union is pursuing a claim against the state for wrongful termination. That, to me, means that Ågren and her union most likely believes that the courts will respect the transport authority’s de facto laws to some extent, and could find in her favour. That is as I see it unlikely even under the model presented in Figure 5. A model that could explain Ågren’s and her union’s social behavior is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6. A third model of the Swedish de facto system of government. The difference compared to the second model is that we have extended the de facto legal domain to include the courts, in order to show that it is under this model reasonable to expect a Swedish court to ascribe some importance to de facto laws passed by the de facto legislative entitiy within an authority. Possibly this requires that the Regering is informed and approves of the de facto laws.

So why should I believe the model presented in Figure 6 to be a plausible one, just because Ågren and her union seems to think it is? Well, Ågren obviously has much more data than I do. She has been a director of government authorities, for years. I know that she knows much more about this than I do. Therefore I ascribe some importance to the models that she could possibly be reasoning from.

But we are obviously reasoning on rather thin ice here. And unfortunately it’s difficult to do experiments within the national security domain. Just look at what unexpectedly happened to Ågren.

Past Personal Experiences Interpreted In A New Way

Now having placed higher posterior probabilities on some alternative models I feel a need to review some past personal experiences that I found hard to explain at the time.

What Happended And What I Thought At The Time

In 2016 I requested redacted copies of some documents from the local police authority. I had reviewed the public laws and believed I had the right to do so.

When I did not receive redacted copies, but instead a strangely worded decision document I was surprised. An e-mail exchange with the authority’s legal department followed. The exchange was very puzzling to me: the legal reasoning seemed to me not at all reconcilable with the public laws. I thought the authority had something to hide, so when I was instructed to appeal their decision to an administrative court I did.

The administrative court found in my favour and ordered the police authority to review the documents, redact the classified information and give me the redacted copies. I thought I would now receive redacted copies.

Instead I received a very long decision document from the authority with more legal reasoning that seemed to me irreconcilable with the public laws. I thought to myself: What could possibly explain this? Could it be incompetence? Isn’t it more likely they do have something to hide? I wanted to know, so I appealed this decision as well.

The administrative court again found in my favour. But this time it did not order the police authority to do the work. Instead the court had itself reviewed the documents, redacted the classified information and created the redacted copies. I received the redacted copies along with the court’s written opinion. I was surprised by this. I thought the court would just issue a clearer or harsher order.

When I looked at the redacted copies I felt disappointed. There was nothing in there that was very interesting. Sure, some information had been redacted, but from the context I could see that it was very unlikely that the originals contained anything I would consider sensitive or interesting.

I was puzzled. Obviously I had been wrong: the authority probably did not have anything to hide. This was not the explanation for their behavior. What could possibly explain it? I felt cheated in some way. I felt there was nothing more I could do to understand why this had happened. I still learned something from the experience though: just because the legal department of some authority is probably wrong doesn’t mean you can infer some simple motive. I thought perhaps they have a very strange working culture.

What I Think Now

In light of the new data regarding Ågren, and the models I have inferred from that data, I think it is possible to understand this experience differently.

Firstly, the lengthy exchange and two court cases may have been the result of a misunderstanding: I thought the public laws should govern our interaction. But perhaps the legal department thought that de facto laws should govern our interaction. This seems unlikely to me of course, but on the other hand the experience itself is unlikely under the standard model of the Swedish system of government. Maybe legal departments are often part of the authority’s de facto legislative entity?

Secondly, I now find it easier to understand why the court did the work itself. The court probably realized that it would be impossible to order the authority to perform the work. Perhaps the court felt that the authority would always perform the work under their de facto laws, and that the result would not be in reasonable compliance with the public laws. Perhaps this is a common occurrence.

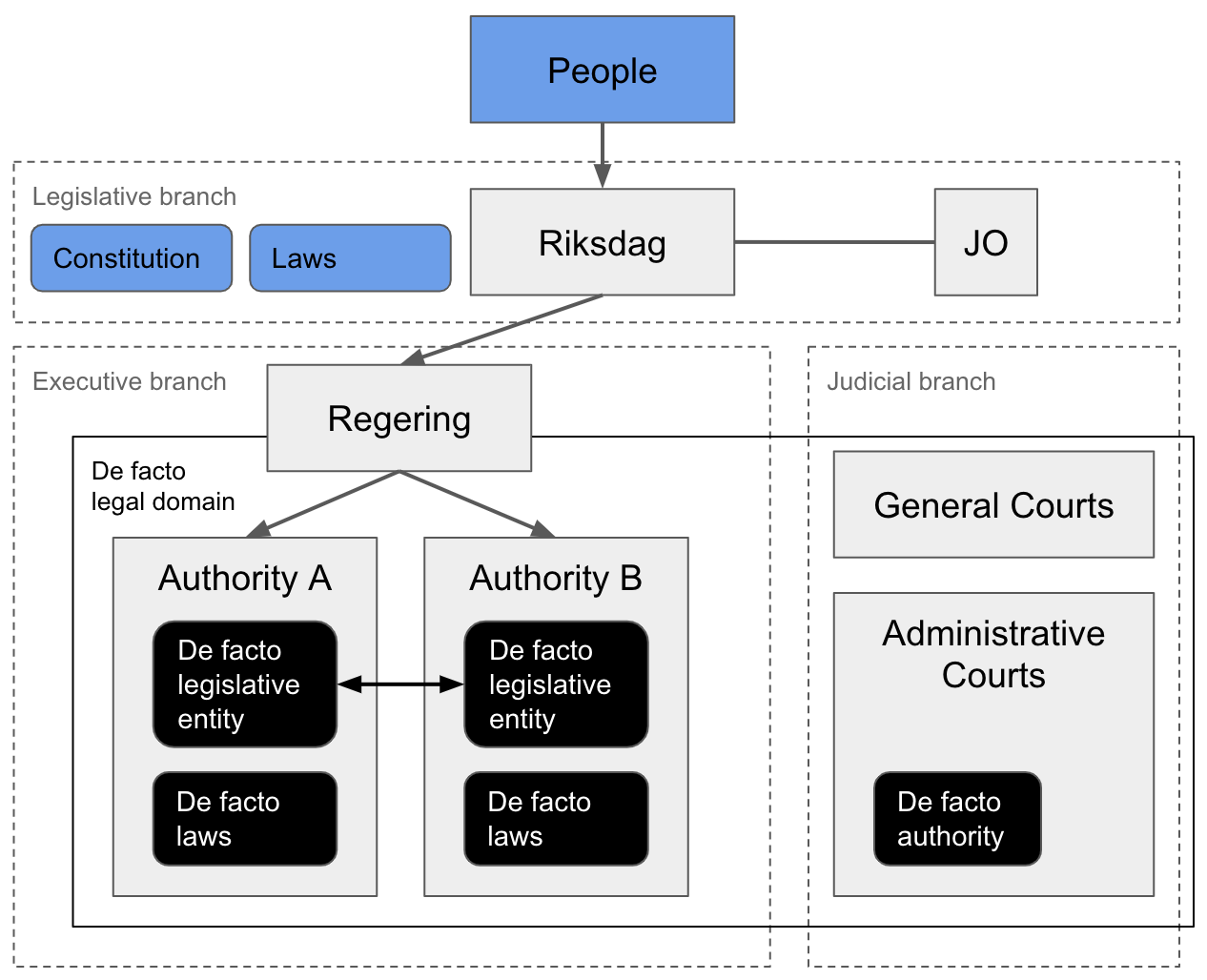

In light of the above reasoning I now place a higher posterior probability on the model in Figure 7. Note that I’m now reinterpreting old data and using it to adjust my posteriors. I’m unsure of how reasonable this is.

Figure 7. A fourth model of the Swedish de facto system of government. The difference compared to the third model is that we have inferred from a reinterpretation of past experiences that administrative courts probably have a de facto authority within them. This entity performs work that authorities should do de jure, but which the court cannot trust them to do (because they are known to operate under de facto laws and the work would therefore not be done in reasonable compliance with public laws). In this model it should also be considered likely that the legal department of the authority is part of the de facto legislative entity. Their job is primarily to get the people and the courts to comply (in a de facto sense) with the authority's de facto laws. When this succeeds the de facto legal domain is extended to include the courts.

Personally I feel that Figure 7 could quite possibly be an accurate and useful model of the Swedish de facto system of government, but that inference is based on much more data than can be presented here. I don’t think you should take my word for it, unless you feel like I felt above regarding Ågren’s possible beliefs.

Future Work

I think any rational agent that feels a lot of uncertainty about what models of reality are correct, and also that reducing that uncertainty would have its benefits, should be looking for more data. I’ve therefore sent an e-mail to the Swedish Labour Court asking for a list of documents and any recordings from Ågren’s ongoing case.

I’ve also sent an e-mail to the administrative court of appeals in Stockholm (“Kammarrätten”), asking for copies of the documents from my own two court cases. I haven’t kept good records of these, and it feels reasonable to me to review them again in light of the alternative models inferred here. They sure cost a lot of taxpayer money, needlessly.

I also sent off a couple of requests for documents concerning de facto laws and the functioning of the de facto legislative entities at some authorities. Maybe something interesting can come of this.

I’m also hoping for a tweet or two, to feel more comfortable with this analysis. Cognition is a social thing you know. Please get in touch if you have any thoughts on this. If you don’t have Twitter you can email me at bjorn@openias.org.

I plan to follow up this post with one describing a single proposed model, and the data that supports it. But I have a lot of plans. Can’t make any promises.